New housing developments in San Clemente over the years have led to more home ownership in the area. Its impact has had an unintended consequence on schools, according to San Clemente High School Principal Chris Carter.

As homeowners grow older and stay in the neighborhood, their children grow up and eventually graduate or otherwise age out of the public school system.

“People bought their homes. They’re not leaving,” Carter said.

The area’s aging population has, in part, led to a decline in Capistrano Unified School District’s student enrollment.

A review of CUSD’s enrollment numbers from recent years reveals that the district has seen a continual decline, which educators attributed to a variety of factors—including the aging residential population, as well as upheavals from the COVID-19 pandemic.

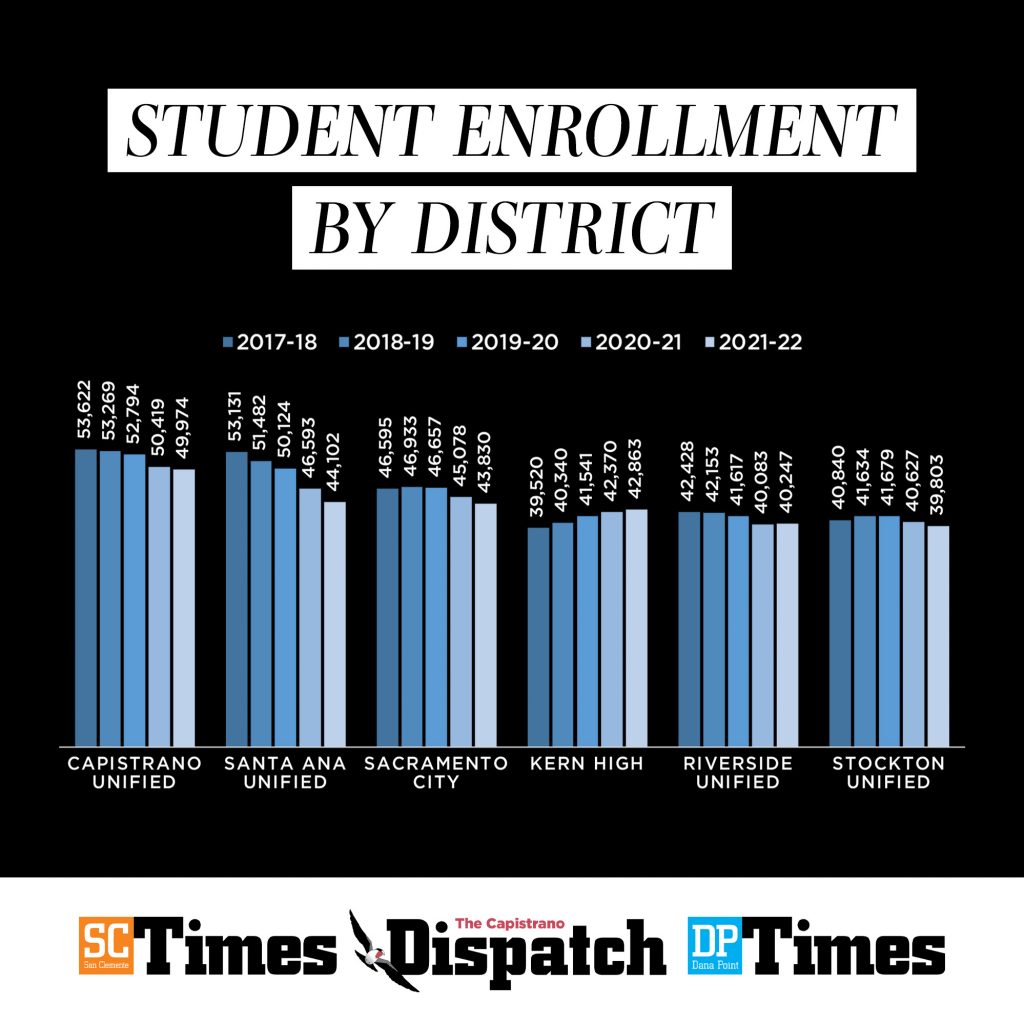

In the five-year period between the 2018-19 school year and the current academic year, CUSD experienced a roughly 21.4% reduction in student enrollment, according to data compiled from Ed-Data, an online resource of fiscal, demographic and performance data for K-12 schools.

DECLINING ENROLLMENT

For the upcoming 2023-24 school year, CUSD projects to have 40,939 students enrolled, down from the 41,854 students in classrooms this school year.

Since the 2018-19 school year—when student enrollment was at 53,269—the district has experienced a gradual decline each passing year, dropping to 52,794 in 2019-20; 50,419 in 2020-21; and then 49,974 in 2021-22.

Carter said local educators have anticipated the decline for some time.

“We knew that decline would hit us in the high school,” he said.

It’s a trend expected to continue for the next 10 years, according to Carter.

CUSD is not alone in seeing a decline in student enrollment. The shift follows a statewide and national trend. A news release put out by the Orange County Department of Education this month said California’s public school enrollment has dropped for the sixth consecutive year, though data released by the state Department of Education suggests the declines are slowing.

“According to statewide figures, the number of TK-12 students in public schools fell by 0.67 percent for the 2022-23 academic year, a decrease of 39,696 students from the previous year,” the news release said. “By comparison, enrollment was down 1.84 percent in 2021-22 and 2.6 percent in 2020-21, the first year of the pandemic.”

Dean West, associate superintendent of Business Services for the Orange County Department of Education, said countywide enrollment peaked near 2003 and plateaued through 2012.

“After that, declines persisted through grade levels,” West said. “Those declines accelerated in 2021, and the state forecasts declining enrollment over the next decade.”

A WORLD UPENDED

Dana Hills High School Principal Brad Baker said the decline was already projected by the time he was hired in 2019. The decrease was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, because the health crisis upended the usual ways public schools operated, which in turn may have convinced some frustrated parents to turn to private or charter schools instead, Baker said.

“I don’t think you can point your finger at one thing,” Baker said.

One parent who pulled their kids out of CUSD altogether after the pandemic upheaval is Chris Mattingly. Mattingly, who went to San Clemente High for his junior and senior years in the 1990s, previously had his older son enrolled in Orange County Academy of Science and Arts (OCASA) College Prep, a charter school in San Juan Capistrano.

Mattingly and his wife were one of the first families to send their kid to OCASA when they heard the school was starting in 2020. They liked what the school stood for: more one-on-one instructional time for students and a curriculum that uses student projects to prepare children for college and careers.

However, when the COVID-19 lockdown hit California and elsewhere, they pulled their son out because they found themselves able to spend time with him while they were working from home and traveling. Mattingly’s son was unable to do hands-on activities in school, which was a big selling point with OCASA.

Mattingly and his wife work remotely and travel full-time in an RV. Their son is now enrolled in an online private school, where Mattingly said he is thriving.

“We have a lot more time to spend exploring places, like national parks,” Mattingly said.

The couple also has time to get their son in front of workers in the tech industry, which he’s drawn to, for a potential internship opportunity.

Alex Zhao is the advisory student board member for the CUSD Board of Trustees. When asked his perspective on the decline in student enrollment, he also said the pandemic showed learning can happen online and not necessarily in person.

“But, of course, there is also the perspective that constantly changing conditions—especially ones caused by COVID-19—may have put families in tough situations where students perhaps do not have the means to go to traditional school, or for some other factor or reason,” Zhao said.

“One should also consider the fact that there will always be a population of students and parents who are discontented with certain district policies and have chosen to leave the district in favor of home schooling or some other schooling alternative,” he continued.

Baker said Dana Hills is in its fourth year of declining attendance and has decreased by a few hundred students overall since then. The school is projected to drop by even more next year, he said.

NO END IN SIGHT

Interim Superintendent Clark Hampton said the phenomenon is normal and expected, given the housing developments built within South Orange County over the years and homeowners not leaving the area after their children graduate.

For instance, what’s happened in San Clemente is expected to eventually happen in neighboring Rancho Mission Viejo, where new homes are being built.

“When you build new homes, you get a spike in enrollment,” Hampton said. “If you fast-forward 15 years from now, you will see a decrease in Esencia enrollment.”

The declining birth rate across the country adds to the trend, Hampton said.

The fall in student enrollment also mirrors an overall drop in Orange County’s population.

“Orange County’s population declined from 3,169,542 in 2021 to 3,162,245 in 2022,” a recent Orange County Community Indicators report said. “This decline, which represents less than one percent of the county population, does reflect increasing outmigration due to the county’s increasing cost of living.”

Pointing to the report, West notes that since June 2012, home prices in Orange County increased by 123%, reaching a median home price of about $1.27 million in June 2022.

“This means that an Orange County homebuyer would need a minimum qualifying income of $250,000 in the first quarter of 2022, while first-time home buyers would need a minimum qualifying income of $157,500 for a home with a median price of $1.071 million,” West said.

THE COST OF ENROLLMENT

While Hampton said the enrollment decline is nothing dire, a decrease in enrollment can subsequently mean diminishing funding for school districts because funding depends on the number of students who attend school.

“The impact is you need to start making budget cuts,” Hampton said.

Currently, CUSD has been able to mitigate funding cuts through pandemic relief funds issued by the federal government—though that is a one-time money source.

Proposition 98, which voters approved in 1988 to require a minimum of the state’s budget to be spent on education, is helping maintain funding levels in the short term, West said.

“However, declining enrollment and low average daily attendance rates due to absenteeism are expected to leave districts with fewer resources, particularly when you factor in the reported COLA—or cost-of-living adjustment—increases,” West said.

CUSD is evaluating school capacity and demographic trends and projections as the state works through finalizing details on California’s upcoming education budget, Hampton said.

Diminishing enrollment can impact daily school operations in numerous ways, including less participation in extracurricular activities.

“Athletes will start to decline,” Carter said. “Musicians will start to decline. Programs will be smaller.”

Filling multiple advanced placement courses for physics or other subjects can also be harder, Carter said.

Baker said the decline can impact how Dana Hills High handles staffing, which can include having a smaller number of school employees as time goes on.

“That’s the unfortunate part of declining enrollment,” Baker said. “We lose good staff.”

A silver lining, though, has been small class sizes, Baker said.

“That’s going to be extended for the next few years,” Baker said.

The school’s sports teams have done a “great job” competing, and there haven’t been noticeable detrimental impacts on daily school operations, Baker said.

“I’m extremely proud of our results with grade and testing data,” Baker said. “Regardless of losing kids last year, our staff has done a great job.”

Zhao, who attends Capistrano Valley High School in Mission Viejo, said his school has not been hit too hard by the impact of dwindling enrollment.

“Overall, it’s a tough situation that even, as a student, I couldn’t say how to keep my peers at school or in the district, but I think it’s just about making school a place that students want to go,” Zhao said when asked if he has any mitigation strategies or solutions in mind.

“Whether improving facilities or opening specialized education programs or classes, these are all an appeal to students and may be able to help with enrollment figures,” he continued.

School districts, county offices of education and charter schools—collectively known as local educational agencies, or LEAs—may deal with declining enrollment differently, depending on their specific circumstances, communities, and experiences, West said.

“Some LEAs are indicating they may need to look at closing schools with low enrollment. Others are leveraging lower class sizes to provide added services in the classroom,” West said. “Much of this is based on one-time allocations or equity funding within the state’s Local Control Funding Formula, which was designed to channel more resources to students with the greatest needs.”

For now, San Clemente High is moving forward.

“The campus still feels packed when you walk around,” Carter said. “It’s positive. It’s buzzing.”