Dick Metz spent plenty of time in Hawaii, riding the waves with locals, opening Hobie Surf Shops and starting his own surfwear brand before coming home and eventually founding a museum to preserve the sport’s history.

By Sharon Stello

As a surfer, Dick Metz was naturally drawn to Hawaii, a place with big waves and iconic surf culture.

Several years before his surf trip around the world that helped to inspired the film “The Endless Summer,” the lifelong Laguna Beach resident traveled to Hawaii to hang out with his friends, Walter Hoffman, Charles “Buzzy” Trent and Gordon “Grubby” Clark, who were stationed there as part of their military service. And Metz enrolled in graduate school at the University of Hawaii though the GI Bill: He was signed up on paper, but didn’t attend classes, preferring to spend his time surfing. He sailed over on the SS Lurline because it was cheaper than flying.

So he arrived on Oahu in 1951 and lived with his friends—who weren’t required to stay on the military base—in a Quonset hut in Makaha during winter, moving to Waikiki in the summer. “I’d surf all day, but they had to go to work and, when they’d get off work at 5, we’d all surf and be together and have dinner,” says Metz, who recalls receiving $26 per week from the GI Bill. “… That doesn’t sound like very much now, but rice and beans and chili, fish, a bowl of that, I don’t know how much it was, but like 50 cents or something. So, for $26, I was living really good.”

Metz, now 93, remembers arriving in Hawaii with his own, brand-new balsa surfboard (before foam was used). “I had to go up to Santa Monica and have Matt [Kivlin] make it,” Metz says. “There were no shops. He was sitting under a tree at the Sip ’n’ Surf bar in Santa Monica Canyon. He made the board—it took about a month. And I took it, brand-new on the Lurline, but we didn’t have board bags then and so it got a little ding on it.”

So when Metz arrived on Oahu, he asked if there was a place he could get some fiberglass and resin to repair the board. Perhaps surprisingly, his friends directed him to a doctor’s office. “And there’s a sign hanging on one house. It said ‘Dr. Dorian Paskowitz, M.D., and Ding Repair,’ ” Metz recalls.

“… I go in the living room. … On one side was a nurse taking applications to see Dr. Dorian Paskowitz and, in the dining room, … were [sawhorses] … that you’d lay your board on to repair it. So he would go from doing ding repair in one room to waiting on a patient with an infection or whatever. So this was 1951. He had just graduated from medical school and was starting out. And he was a surfer. … To make a little side money, he would patch boards and patch people in the same place.”

Metz says he remained friends with Paskowitz, who lived most of his life and raised 13 kids in a motorhome in San Onofre, for more than six decades until he passed away a few years ago in San Clemente. But their first time meeting was to fix Metz’s board.

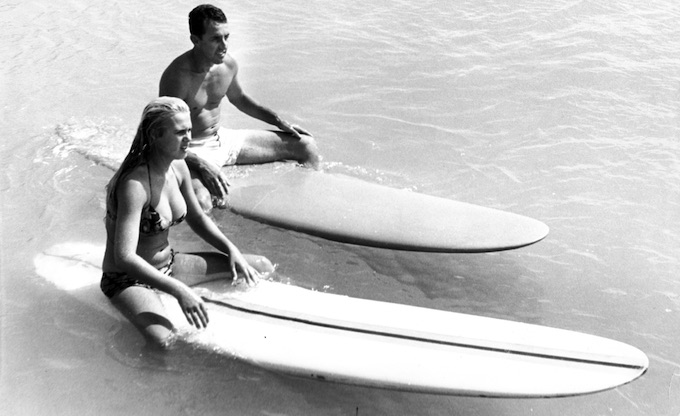

And that board helped Metz connect with the locals while in Hawaii for six months. His board weighed only about 30 pounds and was covered in fiberglass, a material that wasn’t readily available in Hawaii back then. The locals all wanted to try out his board because theirs were heavier. So, of course, Metz let them ride it.

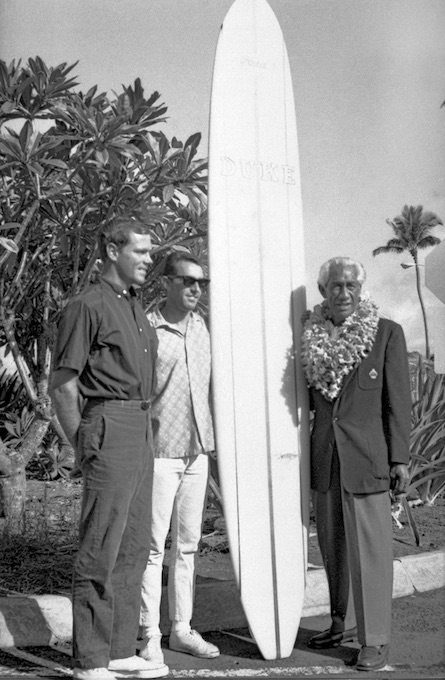

“So that’s how we became really good friends with the local guys. There weren’t very many ‘haole’ guys—[white foreigners]—who could surf then,” Metz says. “So [Albert] ‘Rabbit’ Kekai and … all these local beach boys—Duke Kahanamoku was one of them—we got to know them. And we were good friends. They’d invite us to all their parties. And we’d take out Hawaiian girls and that didn’t upset ’em because we’d let them use our boards. And when I left on the Lurline, I gave my board to the beach boys.”

On the day his ship left, his friends all joined him on board before the Lurline departed. “Walter and Grubby and all my pals are there and here come all the beach boys, like a dozen of them,” Metz recalls. “… And they presented me with an outrigger canoe paddle. And so, they call you brah, which means brother, and they’re giving me hugs because I left them the surfboard. It was a trade-off. … So they’re giving me hugs, they presented me with this paddle, [saying,] ‘You’re a brother, come back any time, you know we love you and you’re one of us.’ And that was a great thing to be accepted by these guys who were really super watermen.”

They were partying and having a good time and then the ship started casting off its lines and a tugboat turned around to start pulling the ship out to sea, but the guys stayed on board. “We go out through the harbor, … we’re looking at Waikiki and the hotels and here comes two outrigger canoes paddling out. So then all the beach boys jump overboard off the bow of the ship and they got in the outriggers and went back to the beach. And we’re throwing flower leis, … [which] means you’re going to come back.

“… I get the paddle they gave me for being a brother and then these guys jump off and the music’s playing and … I’m crying. It was just an emotional, touching moment. I still have that paddle.”

On that first trip to Hawaii, Metz formed a brotherhood with the local guys and maintained a connection with their families. “I’ve been going back to Hawaii all my life and those guys have all passed away now, but their sons are beach boys.”

Surf Style

Another key thing happened on Metz’s first trip to Hawaii. He met a tailor named M. Nii—“a one-legged Chinaman,” Metz says—who sewed some swim trunks for him at a time when surfwear wasn’t a thing. “We were surfing in cut-off Levis. There were no beach trunks that any company was making for surfers,” Metz says.

Nii was based in Makaha and made suits for Chinese and Filipino laborers who came to Hawaii to work in the sugar cane and pineapple fields. So he custom-made trunks on request, with different colors of denim and ribbon stripes down the sides, for $2.50 per pair. Metz asked Nii to add a little pocket to carry a piece of wax—a broken candle, which he used to wax his surfboard since commercial surfboard wax wasn’t available yet. “Over the years, I must have had 15 pairs of M. Nii trunks, all different colors,” Metz says.

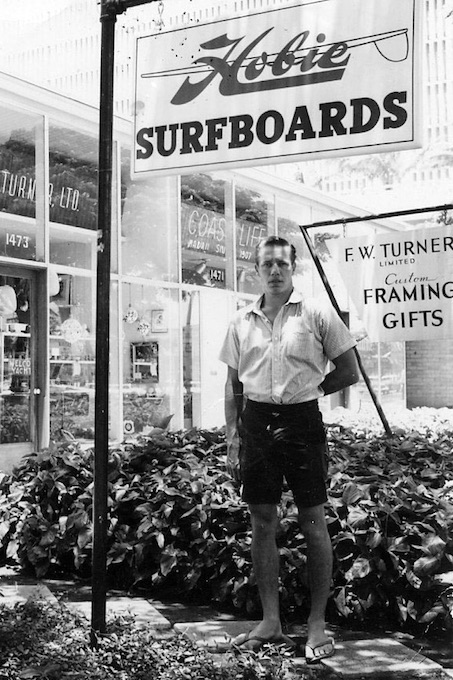

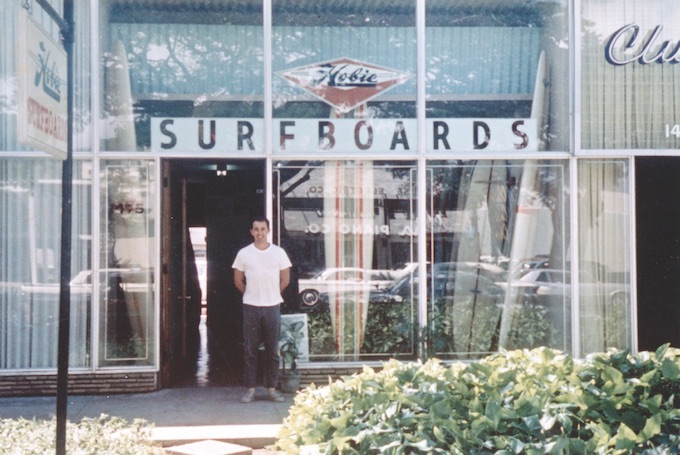

Later, in 1961, when Metz returned from his trip around the world, his friend and legendary surfboard maker Hobie Alter invited him to go to Hawaii and, once there, asked Metz to open a Hobie Surf Shop for him in Waikiki. Metz didn’t know how to run a store, but Alter didn’t seem worried, putting a deposit on a building and heading home to send him some surfboards for the shop.

“This was the first-ever retail store that you could walk in and buy a surfboard and walk out,” Metz says. “Up until then, you went in and gave an order. Well, there was no store. You’d go to some guy’s garage. Like Hobie was doing in his dad’s garage. … But this was the first store in the world that had 50 surfboards—different colors, different sizes. And so, if you flew over there, from the airport going to Waikiki, you could stop at the Hobie shop and get a brand-new board.”

Metz recalls that Alter had made part of an order for Sears, Roebuck & Co., which wanted surfboards to sell in its stores. “So he took 17 out of the Sears order and airfreighted them to me. So I got them the next day or so. … There was a lawn, a little yard in front of that store. So the truck … brought ’em and put them on the lawn there.”

A bunch of Hawaiian kids, who had heard about the store opening, gathered around as Metz opened the box and the surfboards slid out one by one. The kids would say, “Oh, I want that one, I want that one,” Metz recalls. “… Guys are sticking money in my shirt pocket. I didn’t get any of them in the store. I sold 17 surfboards in an hour before I even got them in the store.

“… It just took off,” Metz says. “See, the boards had gotten lighter, … but in Hawaii, they didn’t have them. They didn’t have the material. And so the guys that were making boards there were still making them out of redwood—terrible, big, heavy things. So I could sell them as fast as I could get them.”

Then other manufacturers, like Velzy in Hermosa Beach, California, all started making extra boards to sell if someone didn’t want to wait and didn’t care about having a particular color, Metz says. “So everybody started making extra boards and that’s when surfing started to really blossom and the public got interested in it and it became a real sport. Up until then, … the boards were too heavy—girls couldn’t surf [and] kids couldn’t surf. They couldn’t carry a board, they couldn’t take it home [or] put it on the car.”

Birth of the Surf Industry

Pretty soon, a company started making surfboard racks for cars, which the Hobie store sold along with boards and repair kits that Metz created with resin and fiberglass, as well as pieces of wax—a square of paraffin wax used for canning at the time—before commercial surfboard wax came about. Then surf trunks and T-shirts started filling the shelves including shirts with a Hobie logo that said “Dana Point, California,” which Metz changed to “Honolulu, Hawaii,” and they began selling like hotcakes.

“I sold thousands of them because that showed that you’d been to Hawail,” Metz says. “So all of a sudden, on the beaches in California, you’d see ‘Hobie, Honolulu, Hawaii,’ and that gave you a certain status. The ideal, cool, cool status was a pair of M. Nii trunks and a Hobie Honolulu T-shirt. That right away said, ‘I’m a big deal, I’ve been to Hawaii, I’ve surfed bigger waves [and] I’m the coolest dude in town.’ ”

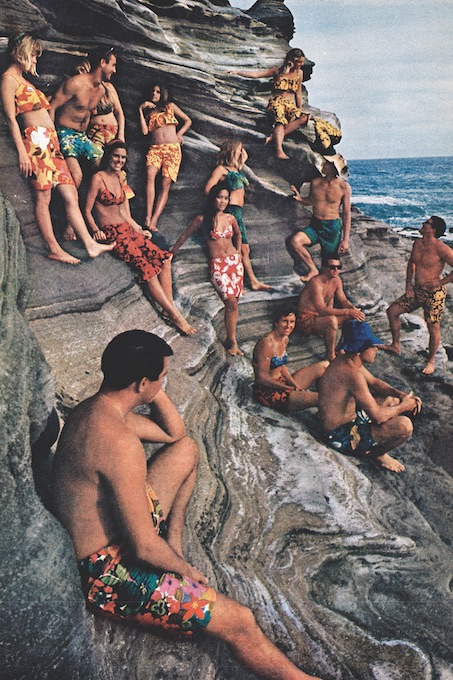

“… That started the surf industry as we know it because then manufacturers came along,” Metz says, mentioning brands like Hang Ten, which made corduroy shorts. Metz even got in the business, starting a company called Surf Line Hawaii with design partner Dave Rochlen, which made Jams trunks and aloha shirts. The brand was a hit and even made the cover of Life magazine. “It just went crazy,” Metz says. “So we were all of a sudden, we were the biggest deal in town.”

Metz lived in Hawaii for 30 years, but came back to Laguna all the time, going back and forth, and opened more Hobie stores in Florida—which didn’t work out because they were too far away to manage properly—and other islands in Hawaii, which were close enough to oversee. He also took over the Dana Point store and opened locations across California from Laguna Beach up to Santa Cruz. “So this is how we became the biggest surf shop company in the world,” Metz says. “We had 22 stores.”

Alter went on to invent Hobie Cat catamarans, the Hobie Hawk radio-controlled glider, scratch-resistant polarized sunglasses and more, which would eventually be owned by different entities. But Metz remained in control of Hobie Sport, which ran the surf shops. He was involved with the Hobie stores for 50 years, off and on. “I sold them four times … and the guys couldn’t run ’em and I got ’em back four times,” Metz says. “And so, every time I thought I was retiring, I got the stores back. And I knew them so well, it was easy for me to take them back.”

Part of the problem was understanding the Hawaiian market as it demanded a different range of sizes than in California. “In Hawaii, it’s totally different,” Metz says. “You’ve got great big Samoans and you’ve got little skinny Chinese kids, so those size scales and color scales [from California didn’t work].”

Eventually, the fifth time Metz sold the stores and they went broke, he decided not to buy the company back. So local Mark Christy bought the Dana Point and Laguna Beach stores out of bankruptcy and still owns those remaining stores.

As Metz looks back on his years working with Alter, he explains it was a different time. “At his funeral, when I got up and gave a speech on Hobie, I said, ‘Hobie and I never had a written contract. I don’t even know if we ever shook hands over it. Hobie just used to say, ‘If it’s good for you, it’s good for me.’ … And that was the great relationship you can’t have in today’s world. … I mean he trusted me, I trusted him and that was enough said. I think that’s important, there again showing the difference between the culture, the lifestyle, the attitudes, the way we lived then [and] how we have to live now. It’s so different.”

Preserving History

During his time with the Hobie shops, Metz had collected a bunch of old surfboards that he used as decor in the stores above the clothing, wetsuits and surfboards.

“So, when I sold all the stores, I didn’t sell the surfboards,” Metz says. “And I shipped them all from Hawaii over here. And then I started a foundation called Surfing Heritage Foundation. In Laguna, I rented—not an office, … [but] a desk within an office … across from the art museum.”

Metz says the nonprofit was started in 1999 and didn’t have a building until around 2003. And then, thanks to a fundraising campaign in which 100 friends each donated $6,000, the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center opened in its current building in San Clemente in 2004.

At the same time, Metz says, he became friends with Spencer Croul, a surfboard collector whose dad owned the Behr paint company. “See, I had old surfboards and Spencer had collected a lot of newer ones. So when we added his collection to my collection, it made the best collection in the world, by far,” Metz says.

And Metz wanted to share it with the world. “I thought, I’ve lived this whole period and watched surfboards grow from the heavy wooden ones … to the present foam ones of 5 pounds, saw the surfboard industry change, the shops change [and the introduction of surf] clothing,” Metz says.

The Surfing Heritage and Culture Center’s museum features a large room filled with surfboards to show their evolution through time, from Kahanamoku’s personal boards to modern, high-performance boards that have been ridden by recent world champions. And other special exhibits come and go, from women’s influence on surfing to the shortboard’s evolution, the impact of surf shops on local culture and surfing in cinema. “We’ve had trunk shows in the museum—how trunks have evolved from M. Nii’s to present-day trunks. T-shirts, obviously I have all those, [and] aloha shirts.

“… I’ve been involved in it since day one and it just seemed like the public should know about it [and] be aware of it. The surf industry should be aware of it. And so I wanted to start a museum that would save these artifacts like every other industry has.”

The center also serves as a repository of magazines and books about surfing, which is often used by researchers. “It’s an archive of the whole industry,” he says.

Currently located inland a ways, the center’s building is owned free and clear so there’s no need to move, but in the future, Metz would like to have at least an outpost in a more coastal spot with greater visibility, perhaps in Dana Point or Laguna Beach. “I think people should know. … Laguna was a fundamental part of how it all started. Hobie Surfboards started here. Other surfboard makers were here,” Metz says, explaining how they moved to unincorporated Dana Point once fiberglass, resin and foam started being used because the zoning rules were more lax for manufacturing there.

Of course, surfing took off and is now embraced around the globe, and Metz witnessed its transformation firsthand.

“Surfing has had a huge impact on world culture and lifestyle,” he says. “I mean guys in Europe and Kansas and Africa are wearing surf clothes. Through the movies and the magazines, they all want to be surfers. It had such a huge impact, I thought it was really important to tell that story.”