Dick Metz grew up during surfing’s heyday in Laguna, experiencing the sport’s evolution firsthand.

By Sharon Stello

When Dick Metz started surfing as a kid in the 1930s, his board was a heavy piece of redwood that he would leave at the beach because it was too cumbersome to carry home or for anyone to try to steal.

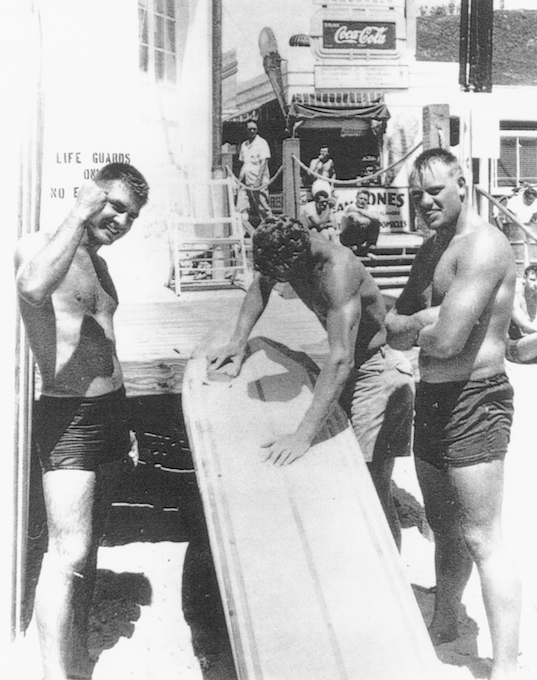

“George ‘Peanuts’ Larson … made this board in front of my dad’s restaurant on Main Beach and I’ve had it ever since,” says Metz, now 93 and a lifelong Laguna Beach resident. “This was my first board. It weighed 109 pounds. He made it and taught me how to surf. He was a unique guy—I could tell you a million stories about him.”

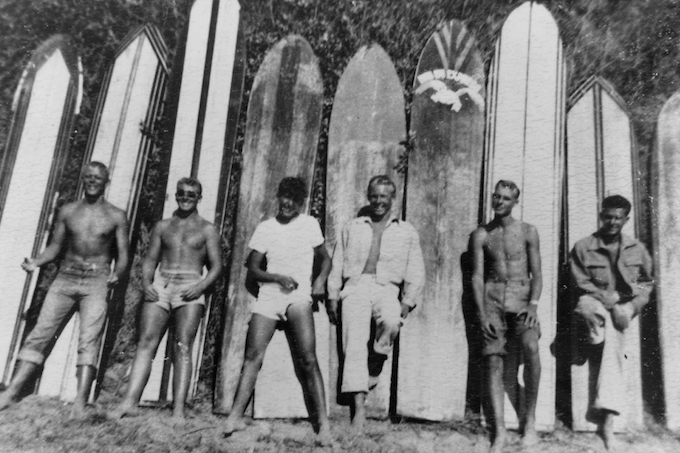

Over his lifetime, Metz has seen the transformation of surfing and surfboards, which grew lighter and more maneuverable as materials improved. For a while, boards were hollowed out to reduce the weight. Old-time photos show guys standing with their boards upright on the beach, but they weren’t just striking a pose.

“We’d put a wine cork in [a hole at one end, and] … you brought it up on the beach when it started to sink,” Metz recalls. “… If it sunk, you’re done, it’s gone. You had to get it to shore and then it would be so heavy, you could hardly get it up [and] pull the wine cork out. …So you’d see boards standing on their tailblocks so they could drain.”

After it dried out, the cork would go back in the hole “and then you could go surf for another 15 minutes before it had to come out again,” says Metz, a surfer whose world travels helped inspire the film “The Endless Summer” and who went on to open and manage Hobie Surf Shops across the country and establish the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center in San Clemente. But the progression of surfing isn’t only a display in his museum; Metz experienced the evolution firsthand.

Building a Better Board

It wasn’t until World War II that fiberglass and resin were developed and then used on balsa wood surfboards in the following years. In addition to waterproofing the boards and making them lighter, these new materials allowed a fin to be added for quick turning.

“So the weight went from 80 to 100 pounds down to 40 … and, all of a sudden, you could put a fin on it with fiberglass that was deep enough to allow you to turn. This changed everything,” Metz says.

“… [Before fins,] you had to drag your foot as a surfer or you’d reach down on your knees and put your arm in the water and make the board turn, but it was real slow turning, so you couldn’t surf waves like at Brooks Street, for example, or Oak Street,” Metz says, “but San Onofre you could surf—it’s a slower-turning wave.”

Next, surfboards moved into the era of lightweight foam cores to replace balsa wood, which was easy to shape but soaked up water like a sponge and was in limited supply as it only grew from Central America down to Bolivia.

The goal, then, was to create a foam that was dense with a smaller cell structure than styrofoam, and Hobie Alter was instrumental in this effort. Metz met Alter while attending Chaffey College in Rancho Cucamonga—Alter was younger and attended the adjacent high school that shared a gym—before running into him again years later on the beach in Laguna. “His dad bought a house on Oak Street and I went surfing there all the time, so it rejuvenated our friendship,” Metz says.

In his dad’s garage, Alter and Gordon “Grubby” Clark worked to perfect the foam needed to fill their surfboards, with Metz assisting as the “pourer.” “He bought a chemistry set and kept changing the chemicals and made a high-density polyurethane foam,” Metz says. “And it took him a year or better to even start to get it right.” The mixture was stirred in a bucket, then Metz recalls pouring it into a cement-and-steel mold. But youth and inexperience meant there were a few factors they didn’t consider.

“We didn’t know … the temperature and the humidity would change from the morning to the afternoon [and] one day to the other,” Metz says. “So these boards were like a waffle that didn’t have enough dough with these empty spaces in there. These left big pock marks and it was expensive to do the foam and we couldn’t throw it away, so we put Bondo in those holes and then we’d call these Easter egg boards: They were blue, white and kind of a pink color—you had your choice—but they covered up these big blotches that were in the foam.”

It wasn’t until the early 1960s that they achieved the recipe for a foam without these blemishes that allowed Alter to popularize the fiberglass-coated polyurethane core surfboards.

“We finally figured out how to control it and mix it better and be in a controlled environment so it wouldn’t change the composition of it,” Metz says. “All of these were steps along the way.”

Learning From Legends

Metz had started surfing around age 6 with guidance from two older Laguna guys, Larson and Brennan “Hevs” McClelland. Both surfers and well-known locals, Larson also shaped boards while McClelland was a lifeguard who served as the announcer for early surf competitions in the area and went on to establish the U.S. Surfing Association in 1961. But back in the day, wherever they went, Metz went, and he picked up a passion for surfing along the way.

“They were 10, 12 years older than I was and it was during the Depression. People didn’t have jobs and people were literally living on the beach,” Metz recalls, adding that Larson and McClelland had built a shack on the sand below the spot where Las Brisas is now, using wood that washed up from the broken pier. “… They went out surfing and diving to get abalone, to get lobster, and then they would bring it to my dad [at his diner] and trade it for beer or a hamburger or whatever they wanted. So one day, my dad said, ‘I’m kind of worried about my kid. If you’ll watch him, I’ll give you a burger and a beer at the end of the day.’ … I was their meal ticket.

“They just kind of took me wherever they were going. … They’d take me out on the boat and then we’d go to San Onofre and Doheny, surfing. And they had an old Model A Ford and they’d put the [surf]board in the rumble seat along with me. … Because I was a little kid, they’d start tandem surfing with me. They could lift me up; I probably weighed 50 pounds or something. And then as I grew, I just started surfing. … I didn’t pester them too bad, I guess, and we were friends for life.”

Back then, surfing wasn’t very popular because the boards were heavy, wetsuits hadn’t been invented yet and the Pacific Ocean was cold. Plus, guys were more interested in playing sports like football and baseball. But as boards became lighter, interest grew. People started to have money and time for recreation after the war; servicemen returned and began demanding more time off, changing the workweek from six days to five. With a full weekend, they could hop in the car, drive to the beach and try catching a wave.

“This is when surfing took off,” Metz says, noting that lightweight boards helped fuel the craze. “Girls could start surfing, young kids could surf. So all of a sudden, in the ’50s, it became a real sport. … Boards were lighter and clothes came out that surfers could really wear, and wetsuits. … It started in the ‘50s, but … the ’60s were really the growth years

in surfing.”

The Trip of a Lifetime

After college and a brief stint in the Army, Metz was managing a liquor store in Huntington Beach (at the behest of his dad) when he wasn’t out surfing or poring over magazines that showed exotic destinations he was itching to visit in person. Metz says he sold the shop’s liquor license to a guy from Disneyland—which was being developed at the time—paid off his debts, sold his car and set off hitchhiking with a rucksack and $2,200 in traveler’s checks. He began this three-year global expedition in 1958 from the curb in front of The Sandpiper Lounge in Laguna, where he had worked as a bartender.

“I wanted to go to Tahiti. I wanted to go to Australia, because I knew there had to be surf in Australia. I wanted to go to Africa and see wild animals, elephants and rhinos and wild tribes. … I wanted to go to the Olympic Games in Rome in 1960. … And I wanted to go run with the bulls in Pamplona, Spain, “ Metz says. “Those were the five things. I had no idea how I was going to get to any of them.”

There were no airplanes that flew to Tahiti; the only way to get there was by ship. He had read that if you got to the French embassy in Panama, you could get a ride on a French Foreign Legion ship, which stopped in Tahiti (a French possession at the time) on the way to taking troops to the French-Indochina War in what’s now Vietnam. “You never know when the ships are going to come,” Metz says. “It’s not like they’re scheduled. And so I just took a chance.”

To be continued…