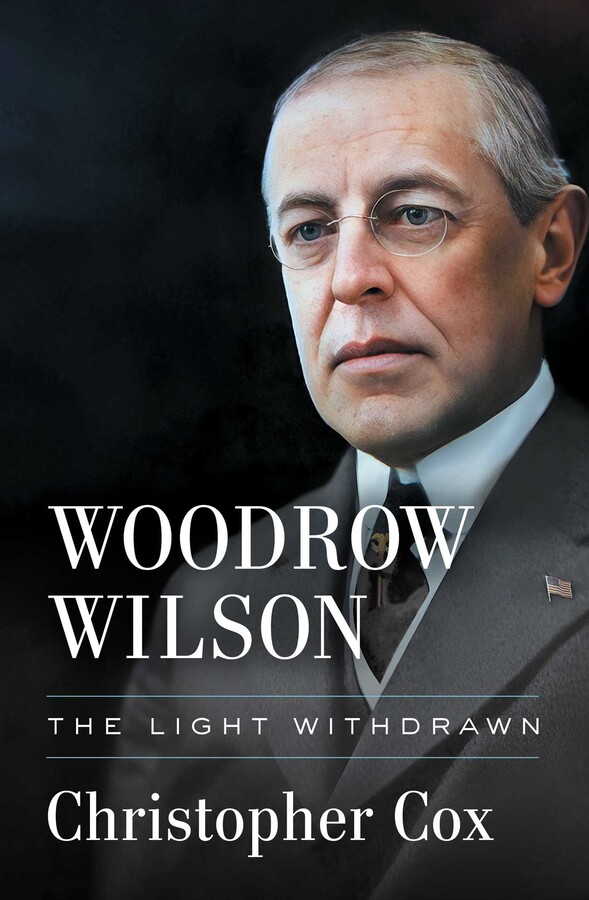

Editor’s Note: Newport Beach’s Christopher Cox has a long history in national politics, becoming the fifth-ranking leader in the U.S. House of Representatives, chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, senior associate counsel to President Ronald Reagan, and working with four U.S. presidents. Using his vast knowledge about how the government works, he wrote “Woodrow Wilson: The Light Withdrawn,” published recently by Simon & Schuster.

Currently, Cox is a Senior Scholar in Residence at the University of California, Irvine, a Life Trustee of the University of Southern California, Chair of the Rhodes Scholarship selection committee for Southern California and the Pacific, and a member of several nonprofit and for-profit boards. What follows are excerpts from his book about Wilson’s opposition to women’s right to vote:

The 1912 presidential election took place in a very different United States than had existed more than six decades earlier, when hundreds of women and men packed the pews and galleries of a nondescript chapel in Seneca Falls. Now in the second decade of the 20th century, the country was unabashedly modern and urban…a whirlwind of “speeding automobiles, streamlined trains, racing ticker tape,” as Sergei Eisenstein would later describe this period. …

The Chicago Coliseum reopened its doors to its second national political convention in six weeks on Aug. 5. Teddy Roosevelt’s newly concocted National Progressive Party was already popularly known as the Bull Moose Party, after the candidate’s frequent remark during the Republican convention: “I feel like a bull moose!” … “The greatest applause which the Colonel received,” the New York Times reported on Roosevelt’s address, “was for his talk about woman suffrage.”

With only weeks remaining until Election Day, the Wilson campaign made a final swing through New York—a Roosevelt redoubt and the greatest mother lode of electoral votes in America. His campaign had assembled a friendly Democratic Party crowd at the stunning new Beaux-Arts opera house in the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Wilson was playing to a packed hall, with both balconies overflowing, and all was going according to script.

As he warmed to his topic—that Republicans had for too long enjoyed a monopoly of power in the White House—a woman in the first balcony rose to her feet. “You have just been talking about monopolies,” she called out to him in a clear voice. “And what about woman’s suffrage? The men have a monopoly of the suffrage …

I am speaking to you as an American!”

The vast majority of America’s 48 million women were being denied the right to vote in this national election by their own states. What was Wilson prepared to do about it?

In truth, Wilson was prepared to do nothing about it. Having exhausted his rote arguments, he slammed the door shut on the entire issue. “I positively decline to discuss that question now,” he told her and his audience.

Throughout the fall of 1917, successive waves of volunteers continued to carry banners in silence to the sidewalk in front of the White House. Each time, they were arrested, summarily convicted of “obstructing traffic,” and shipped off to serve ever-longer sentences…

At the millennium, the Gallup organization asked the American public to name the most important event of the 20th century. Sixty-six percent chose “Women gaining the right to vote”—ahead of landing a man on the moon, the fall of the Soviet Union, World War I and the Great Depression. Only World War II ranked higher.

To Woodrow Wilson in Paris, the final passage of the women’s suffrage amendment in Congress on June 4, 1919, seemed much less significant… Meanwhile, the fight for ratification of the Anthony Amendment was underway. Its progress made headlines almost daily…

On Sept. 3, 1919, a decidedly inflexible Woodrow Wilson boarded a private train for a 10,000-mile journey…

In tandem with Wilson’s treaty tour, supporters of the Anthony Amendment continued to rally legislators in state capitals across the country…

Wilson’s deteriorating health was now becoming apparent even to the public… The presidential special diverted back to Washington where, one week later, Wilson suffered a massive stroke…

He could no longer read, sit in a chair to eat or sign his name. His muscles were weak, his memory faulty. White House chief usher Ike Hoover found him “mentally but a guiser”—a pretender. … For over four months, Wilson remained in seclusion, and the government all but ran itself. …

“He has been ill since last October,” Wilson’s press secretary at Versailles, Ray Stannard Baker, recorded in his diary in late January 1920, “and he cannot know what is going on. He sees almost nobody and hears almost no direct news… Was there ever such a situation in our history!”

With the First Lady and the president’s staff now handling Wilson’s day-to-day paperwork, a few one-sentence telegrams in support of the Anthony Amendment began to emerge from the White House in 1920…

The president was uninvolved. Though he had improved somewhat by the summer of 1920, he was able to concentrate only for short periods and watched movies every day… Ike Hoover, who brought Wilson to the cabinet room in his wheelchair, would watch as the president sat silently for the “so-called” meetings “as one in a trance.”

The telegrams, in any case, were mostly ineffectual. Not since March, when Washington’s approval brought the Anthony Amendment to within one state of the needed thirty-six, had any other state legislature stepped forward to finish the job.

So, when the Tennessee Senate voted its approval on Aug. 13, it electrified suffrage supporters across the nation. The prospects for success in the state’s House of Representatives were tantalizing: a roll call on a preliminary procedural question showed the votes split exactly evenly, 48–48.

The Speaker of the House, Seth Walker, was a Democrat opposed to the Anthony Amendment. If he could be convinced to change his vote, the battle would be won, and the Democrats could claim credit for putting it over the top …

On the day of the final vote, it was another member of the Tennessee House who proved willing to tip the balance. Republican Harry Burn, unlike most of his colleagues, had remained uncommitted… In the midst of the final balloting, a page on the House floor handed him a letter. Just before casting his vote, he opened it. The letter came not from the White House but his widowed mother.

“Dear Son,” she wrote, “vote for suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt.” Recognizing that his vote would determine the outcome, Burn voted “aye”—bringing victory at last to the seventy-two-year campaign for women’s suffrage.

The Susan B. Anthony Amendment, in its original, unadulterated form, took effect immediately on Aug. 18, 1920, with less than ninety days remaining before the 1920 presidential election.