Editor’s Note: Dick Metz is well known in the surfing industry as the former owner of Hobie Sports shops and Surfline Hawaii and for helping reveal the legendary surf spots Cape St. Francis and Jeffreys Bay in South Africa. He was the subject of the documentary “Birth of the Endless Summer,” which aired on PBS SoCal. The Business Journal annual list of apparel companies based in Orange County begins on page 17.

I began surfing Laguna Beach in the mid-1930s when hardly anyone was surfing. The water was cold, we didn’t have wetsuits and the 100-pound-plus boards were not very maneuverable. I’d leave my board on the beach because it was too heavy to carry home.

In 1934, Peanuts Larson made a board in front of the lifeguard tower in Laguna Beach. In his old Model-A Ford, Peanuts would take me to San Onofre and Doheny, the only good places to ride in those days.

In 1958, I got on ships and went around the world. I didn’t travel with a board and instead borrowed them at select locations. When I reached Africa, I got off in Mombasa in East Africa and started hitchhiking all over the continent, arriving in the town of Arusha in Tanganika, which is now Tanzania, and there’s only one road. There were no gas stations, no places to eat and no towns. So, you had to carry a 55-gallon drum of gas in your truck. You had to take your own food and your water. I originally planned to go to Victoria Falls but decided to continue on to Cape Town.

The beach at Cape Town looked just like Laguna Beach with girls in bikinis and guys drinking beer and wine and cooking steaks at barbecues. I stayed there for seven months with a surfer who was a used car salesman at the Volkswagen dealership.

I eventually told him, “Well, I’ve got to keep moving and I’m going up the coast. There’s gotta be some good surfing spots.”

He said, “Be sure and look at a place called Cape St. Francis.”

I hitchhiked up the road about another thousand miles to Cape St. Francis. There was only one building, kind of a little general store and a guy who lived in it. I bought some supplies there and I asked him if I could sleep in his front yard and he said, “Fine.” He had a dog that I made friends with, so I slept there that night. The next day I walked out on the beach. The surf was fabulous, but nobody lived there. I stayed about five days. I also got up to Jeffreys Bay, another fabulous surf spot some 15 miles northeast.

When I returned two years later to California, I showed my pictures to my friends, including Bruce Brown and Hobie Alter. I said, “Bruce, you’ve gotta go where I’ve surfed.” He finally followed my trip with two surfers, Robert August and Mike Hynson, to make the film “The Endless Summer.”

With its recognizable orange, hot pink and brown poster illustrating surfers and their boards, the famous movie celebrated its 60th anniversary last year. I’m proud to say that this iconic film was inspired by my global travels in search of great surf from 1958 to 1961.

Decades later, Richard Yellen, a producer in Hollywood, heard how “The Endless Summer” came about and called me, and eventually took me back to Africa to make a movie about how I discovered those great places to surf. That documentary, “Birth of The Endless Summer,” debuted in film festivals in 2021, played in select theaters in 2023, and aired on PBS.

The Birth of a New Industry

My business journey began when Hobie asked me to run a surf shop in Hawaii, even though I had no experience selling surfboards.

In the early 1960s, Hobie began experimenting with making surfboards out of polyurethane foam and then covering them with fiberglass. They often weighed less than 10 pounds.

Hawaii hadn’t gotten that material yet. So, I took the new ones that Hobie made in Dana Point and had them shipped to me in Hawaii. I sold the heck out of the new boards. Girls and young kids started surfing because they could carry the lighter boards.

When I opened the Hobie stores, we had surfboards to sell but nothing else. I realized right away that we needed other products because the surfboard cost $80 to $100 each. We didn’t have the right clothes to wear. So, I started a clothing company making t-shirts. Just like today, people dress to indicate what sports they’re involved in. People wanted to be recognized as a surfer, so we made special trunks and called them jams. They were made out of Hawaiian prints with wild bright colors and were longer than typical.

Suddenly, I was at the beginning of a new industry. The sport created a whole new clothing industry that grew up in Orange County and still exists here to this day.

I would eventually own 22 Hobie Sports stores, which became part of a popular surfing culture that people wanted to enjoy.

For me, the stores were also a place where old surfboards went to wait for their next life. Guys had these old boards and would take them to the dump. But I had the Hobie stores, so I would tell them, “I’ll save you a trip to the dump, leave them here.”

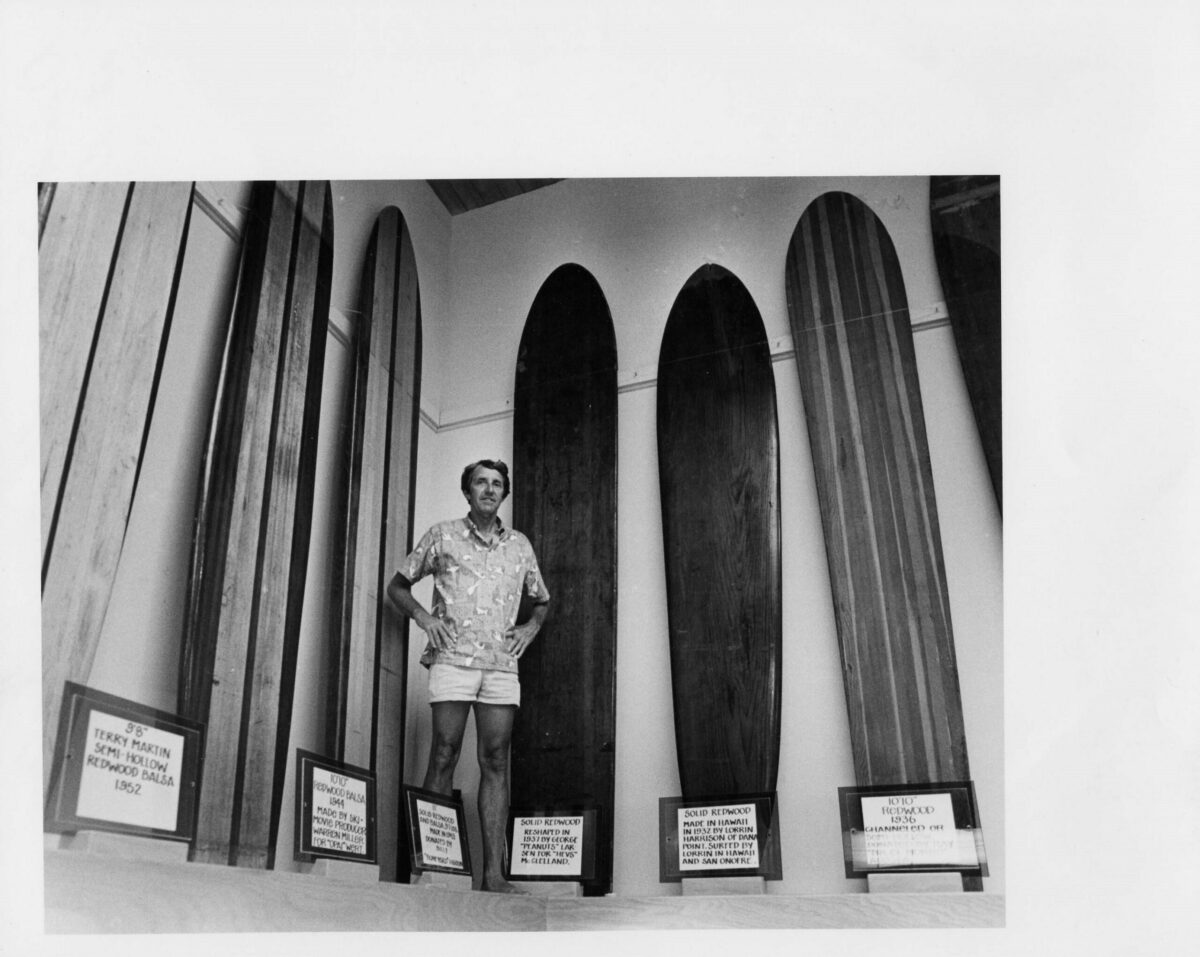

I’d put them in the rafters. I began collecting surfboards and memorabilia when nobody cared about them. Over 20 years or so, I collected many historical wooden surfboards. I even have the board that my friend Peanuts made in 1934. I thought these boards told stories and were important. More than just objects of nostalgia, the surfboards illustrated the technological innovations and elements of a lifestyle that underscored the popularity of surfing.

The Birth of a Surf Museum

In 1999, I founded Surfing Heritage & Culture Center (SHACC). In 2003, Spencer Croul, a surf culture preservationist from Newport Beach, joined the effort and secured our first location in San Clemente. Driven by a vision to document the history of surfing, we combined and cataloged our trove of surfboards and surfing memorabilia and documented oral histories to create the foundation of the nonprofit’s institutional collection.

Our collection drew the attention of The Smithsonian Institution, which affirmed that surf culture had a place in American history when it accepted curated items from us for the National Museum of American History. Some of those items appeared in “Wave of Innovation: Surfing and The Endless Summer,” an exhibition the museum mounted in 2015.

Our donations to The Smithsonian included one of the legendary Duke Kahanamoku’s redwood boards, contributed by renowned board shaper Mike Marshall and his surf-historian wife Sharon.

When we chose a business complex in the hills of San Clemente for our first location, we were looking for enough capacity to house the world’s largest collections of noteworthy surfboards. Now, it’s time to expand to a more visible location where visitors to Orange County and local residents alike can enjoy our world-class collection. We are in the process of selecting a new site.

With the support of my philanthropic partners at the Orange County Community Foundation, we’re about to embark on an exciting new future.

What could be better than stepping out of the museum and walking toward the Pacific Ocean to see its inspiration in real time—local surfers catching waves at one of Orange County’s iconic surf breaks?

The endless summer lives on here in our own backyard.