Dick Metz went on a worldwide wave-riding expedition in the late 1950s that helped to inspire the film “The Endless Summer.”

By Sharon Stello

Dick Metz was itching to see the world—and ride the killer waves he knew must be out there. After growing up in Laguna Beach during the Great Depression and experiencing the evolution of surfing, starting as a young grom taught by local legends, he decided in 1958 to set out on an adventure. With a rucksack and $2,200 in traveler’s checks, he stepped up to the curb in front of The Sandpiper Lounge, stuck out his thumb and waited for a ride.

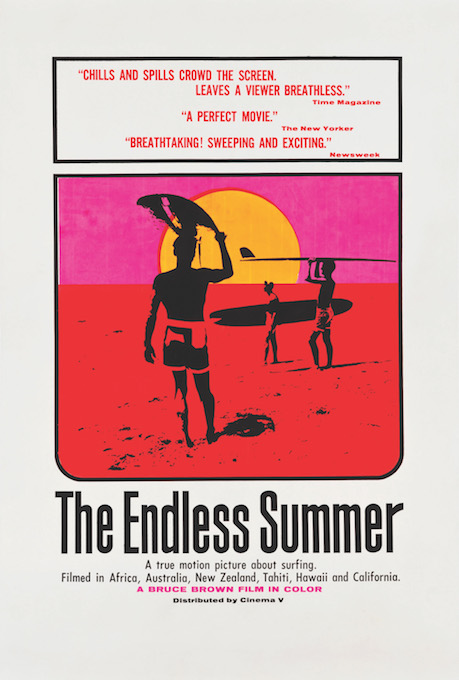

He planned to visit Tahiti, Australia and Africa, attend the Olympic Games in Rome in 1960 and run with the bulls in Pamplona, Spain. “Those were the five things. I had no idea how I was going to get to any of them,” he says. Metz’s world travels, which spanned three years, would help inspire the film “The Endless Summer.” He would go on to open and manage Hobie Surf Shop locations across the country as well as establish the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center in San Clemente—but first, he had to get halfway around the globe in a time when airplanes didn’t fly to his first destination.

His plan, based on a tip he had read, was to reach the French embassy in Panama and arrange a ride on a French Foreign Legion ship, which stopped in Tahiti (a French possession back then) on the way to taking troops to the French-Indochina War in what’s now Vietnam. “You never know when the ships are going to come,” Metz says. “It’s not like they’re scheduled. And so I just took a chance.”

Going Aboard to Get Abroad

Now 93, Metz reflects back on this journey of a lifetime. He got lucky and for the price of $60 for food—oatmeal, cabbage, French bread and all the wine you could drink—he received a 17-day passage to Tahiti. Accommodations were a hammock in the hold of the ship along with military tanks and trucks, with a view of the sky through open hatch covers; he wasn’t allowed to go up on deck. Among the troops he had for company, he recalls former German officers who were given a new identity by becoming legionnaires.

Once in Tahiti, he spent three months surfing and soaking up the local beach life from Bora Bora to Raiatea and Huahine. But then he couldn’t leave because there were no planes or passenger ships there. So he talked his way into a job on a Norwegian tramp steamer bound for Australia, along with another American he had met in Tahiti. “So we went from Tahiti to Samoa, we went to Pango Pango, went to Fiji, New Hebrides, New Caledonia, the Marshall Islands, I think, and finally got to Australia,” Metz says. “He got off and got on an airplane and flew back to LA and I went surfing in Australia.”

But while on the ship, he ate meals with the Norwegian captain and other officers, who wanted to practice their English. And he got a letter of recommendation (which Metz wrote since the captain’s English wasn’t so good) to help acquire jobs on other ships along the way. “He said, ‘I’ll give you the stationery, you write it and I’ll sign it.’ So I wrote a letter that would make you think I was one of the great sailors of the world. And he stamped it and signed it and I still have the letter.”

After surfing for a few months in Australia, he lined up a job on another Norwegian ship and hopped a ride to Indonesia and, eventually, Singapore, then started hitchhiking up the Malay Peninsula to the island of Penang to see the great Snake Temple, filled with large serpents like pythons, venomous black mambas and pit vipers. He then trekked to Thailand, Cambodia, Burma (now Myanmar) and up the Irrawaddy River to Rangoon.

“I was always fascinated by the names of cities,” Metz says. “I thought, ‘Singapore, Rangoon—I mean, those are great names.’ Mombasa, Dar es Salaam. I was just fascinated by the names. So I had to go to Rangoon.”

From there, he ventured across into India, where he stayed in a YMCA in Calcutta (now Kolkata), then hitchhiked up to Benares (or Varanasi), a great religious city, along the Ganges River to New Delhi, the Taj Mahal and on to Bombay. He worked on another Norwegian ship heading to the Seychelles, a group of islands in the Indian Ocean, then on to Zanzibar—a big slave trade hub in the 19th century—then to Mombasa in East Africa, which was then a British colony. “I got off in Mombasa,” Metz says, “and I spent the next year and a half hitchhiking all over Africa.”

African Adventures

Crisscrossing the great continent of Africa on dirt roads, Metz wasn’t sure where his next ride would come from. “I was scared to death,” he says. “I waited 17 days in the middle of Africa waiting for one car to come by. We’re not talking about out here on [Highway] 101 and cars are swishing by. And it’s not a car, it’s a truck. There … [are] no bridges. You’ve got to ford rivers. You have to carry your own gas.”

Often, he’d score a ride with young geologists for the De Beers diamond company, who traveled in groups of four to pan the different creeks and rivers in Africa to determine what minerals were in the various waterways. On their way to cities like Nairobi for food and supplies, they’d pick up Metz, but were only traveling to a camp another 200 miles down the road, for example, so he had to wait there for another truck to come by.

“And so that’s the way it was. I slept out in Africa all the time,” Metz says.”One time, I was out sleeping by a tree and I get up at sunup and I walk over a little knoll about 100 feet from where I was sleeping and there’s a pride of lions sleeping in the dirt there. They could have eaten me and I wouldn’t have had a clue.”

The wild animals weren’t the only threat. Around this time in the late 1950s, the often violent Mau Mau uprising was taking place in Kenya against the British that were colonizing their lands. But, perhaps because Metz looked and dressed differently than the typical white colonist, the rebels didn’t hassle him. Somewhat dark-complected (likely from spending so much time surfing in the sun), Metz wore a big straw hat from Tahiti, shorts and a torn shirt, and sported a big beard. “And the most important thing [is] I’ve got … a pair of sandals made in Guatemala out of tires. And they had sandals made out of tires. And so they didn’t know what I was. You had the black guy and you had the white guy in this uniform and then you had me.”

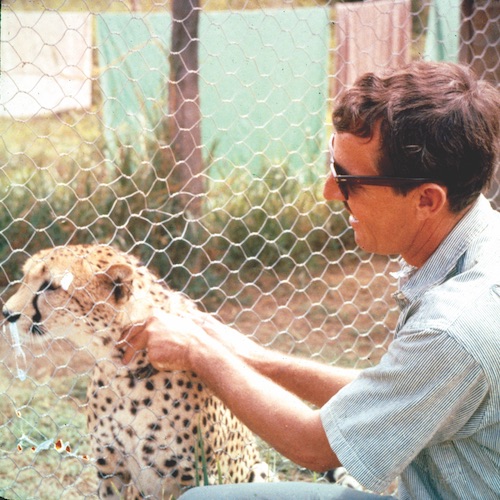

While in Africa, Metz wanted to see the wildlife of the Serengeti Plains, so he got a job working for a safari company, setting up tents for visiting groups, including National Geographic photographers—and taking a few of his own up-close animal pictures. In Tanganyika (now Tanzania), he went to Ngorongoro Crater: At 12 miles across, it’s the biggest extinct volcano in the world. “In the bottom of this crater, there’s water and grass. And these animals, somehow, over the centuries, have gotten over the edge and gone down into the crater and there’s elephants, lions, zebras, antelope, everything down in the bottom. … You can see the whole ecosystem of Africa.”

Aside from the excitement of the wildlife and all these wonders, Metz says there was one drawback to his solitary sojourn. “The good part of traveling by yourself is I got invited to homes all the time, but the bad part is you’re really lonely,” Metz says. “I’m [spending] 17 days in one little African village trying to talk to Africans.”

At one point, he was tending bar in the town of Arusha in Tanganyika and wanted to go see Victoria Falls, which is twice as big as Niagara Falls in New York.

“A guy picks me up—a Danish guy in a truck with gas and food,” Metz recalls. “And he says, ‘Where do you want to go?’ I said, ‘I want to go to Victoria Falls.’ He said, ‘Well, that’s 10 days away, but I’m going right through there so jump in. I want you to help me drive.’ His mom was sick in a hospital in South Africa and he was driving to see her.”

“… He would drive for two hours, then he’d sleep and I’d drive for two hours. We’d trade off. So in the middle of the night on like the ninth or 10th or 11th day, I’m sleeping, it’s 2 in the morning and I’m in the passenger seat, head against the window and he pokes me and says, ‘We’re at Victoria Falls. That’s where you wanted to get out.’ And it’s 2 in the morning. If it had been in the daytime, I would have gotten out in a minute, but I looked out the window, it’s cold, there’s no buildings, there’s no hotels, there’s no gas stations, there’s no anything, but two little huts and a dying fire in the middle of it.”

So Metz decided to see Victoria Falls another time and ride on to Cape Town, South Africa. “Now that decision … changed the surfing world,” Metz says. That choice put him on a trajectory that would change his life and inspire the iconic surf flick “The Endless Summer,” as well as countless surfers to travel the globe beyond California, Hawaii and Australia in search of the perfect wave.

A Serendipitous Meeting

Once they arrived in Cape Town, Metz exited the car about two blocks from the ocean and walked to the water. He spotted a guy and a makeshift surfboard that must have slipped away and was washing around in the shallows between some rocks. So, as common courtesy, Metz went to retrieve it.

“And with that hat on and with the beard and this outfit—it’s the only clothes I had—I said, ‘Is this a surfboard?’ I said, ‘This is the ugliest surfboard I’ve ever seen.’ And he’s real indignant. He’s still in the water and he’s looking up at me and speaking to me in broken English. He says, ‘Who the hell are you and what do you know about surfboards?’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t know a lot, but if you made this ugly sucker, I know more than you do.’ I was trying to get him to laugh. And so, finally, he started to laugh.”

They began talking and the local, John Whitmore, couldn’t believe Metz was from Southern California and had actually surfed there and in Hawaii. Whitmore had fashioned his board after one that was barely visible in a Waikiki beach photo from a Pan American World Airways calendar. There were no surf magazines or movies back then.

Metz ended up staying with Whitmore and his family in their beach bungalow, sleeping on their couch, having barbecues and partying with their friends, dreaming of starting a surfboard business together and falling in love with Whitmore’s sister-in-law, 17-year-old Patty. Metz felt like he was home.

“I’d been in black Africa and all of a sudden, I’m at the beach. Cape Town is the same parallel—[but] in the Southern Hemisphere—that Laguna is and the weather’s the same, pretty much,” Metz says. “The coastline, white sandy beach, rocky point: I thought I was back in Laguna. There’s white girls in bikinis. … [It’s like] I’m back home.”

Eventually, after seven months, Metz left to finish his trip. Whitmore, who worked at a used car dealership, arranged for him to catch a ride with one of the salesmen who was planning a drive up the coast. Metz wanted to check out Cape St. Francis at Jeffreys Bay, which is about 400 miles east of Cape Town. “Usually, where there’s a point, like Dana Point [and] other points, … that creates surf,” Metz says. And his hunch was right. He told the salesman to continue on his journey to Durban and Metz stayed and camped there, reveling in the standout surf spot he had found. “I thought, ‘This is incredible.’ There’s like 20 breaks of surf and it’s really consistent,” he recalls.

“… Obviously other people had been there, but surfing wasn’t a sport in South Africa then. Maybe somebody kind of surfed there, but nobody knew about it. I don’t say that I was the first one there, but I was the first one to kind of bring it to the public’s attention.”

But first, Metz had a few destinations to check off his list, hitchhiking to Durban and up to the Belgian Congo, Uganda and Sudan, then to Egypt to see the pyramids and sailing on a ship across the Mediterranean to Greece. From there, he traveled all around Turkey, Romania, Hungary and Yugoslavia as well as Pamplona, Spain, for the running of the bulls and attended the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome. He also went to Germany, bought a new Volkswagen bug at the automobile company’s factory and had it shipped to New York. Then, he hopped on a ship from the Netherlands to New York, where he picked up the car and drove it back to Laguna.

Once home, he started sharing all these adventures with his friends, presented lectures and slideshows at schools and local service club meetings, and connected Brown with Whitmore for the “The Endless Summer” film, which included many of the locales Metz went to on his global expedition. “He followed my trip, but he did it on an airplane. It took me three years. He did it in six weeks,” Metz says.

Now, Jeffreys Bay (nicknamed J-Bay) is the site of a World Surf League competition each year. “The movie told people about it, so then people started surfing in South Africa,” Metz says. “… It’s the best surfing spot in the world.”

Metz also sent supplies to Whitmore so he could start a surfboard business. He packed up a drum of resin, fiberglass and foam blanks and shipped it to Cape Town, then flew back and showed Whitmore how to make the boards. Whitmore quit his job as a car salesman and made a good living with this new business. “He started making surfboards and the whole sport exploded in South Africa,” Metz says.

They remained friends for life, traveling with their families to visit each other several times until Whitmore developed cancer and died in 2001. But their chance meeting changed the surfing world. And that’s the subject of a recent documentary, “Birth of The Endless Summer: Discovery of Cape St. Francis” from Curtis Birch and Emmy-nominated director Richard Yelland of Laguna Beach in association with Oscar-nominated Bruce Brown Films. The movie follows Metz back to South Africa as he retraces the steps of his original journey and that serendipitous moment with Whitmore.

“It’s amazing how life works out,” Metz says. “… I just happened to come along and meet him. So this is what the movie’s about. The fact that I didn’t get out at Victoria Falls [and] that when I got to Cape Town, I could have … never seen John Whitmore. The fact that, when I met him at the beach, it changed his life. It changed my life.”

To be continued…

Silver Screen Sensation

“Birth of The Endless Summer: Discovery of Cape St. Francis”—a documentary that follows Dick Metz back to South Africa as he retraces the steps of his original journey that inspired “The Endless Summer” film—is poised to make its global release this summer so Metz’s story can be shared with a larger audience. It will also be shown at 3:45 p.m. May 7 at the Porthole Theater at Dana Hills High School as part of the Dana Point Film Festival, which runs May 4-7. “The Endless Summer” will also be shown during the festival, at 4 p.m. May 5 at Salt Creek Beach Park, in honor of the film’s 60th anniversary. (danapointfilmfestival.eventive.org)

“Birth of the Endless Summer,” from Curtis Birch and Emmy-nominated director Richard Yelland of Laguna Beach, in association with Oscar-nominated Bruce Brown Films, premiered at the 2021 Newport Beach Film Festival and has earned an Award of Excellence, Special Mention from The IndieFest Film Awards. (instagram.com/birthoftheendlesssummer)