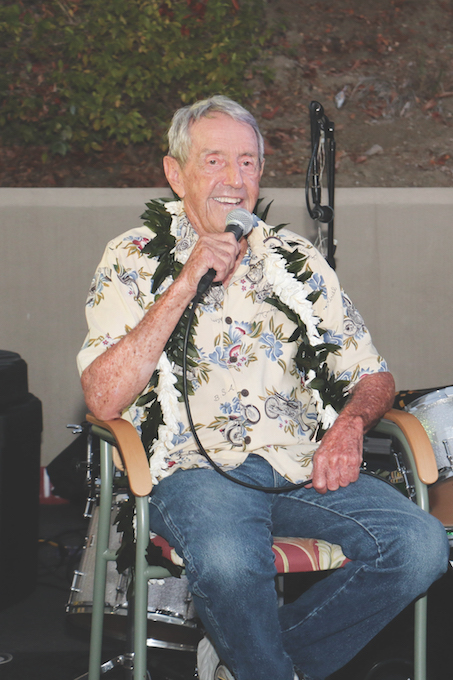

Dick Metz shares his recollections of growing up in this beach town before World War II.

By Sharon Stello

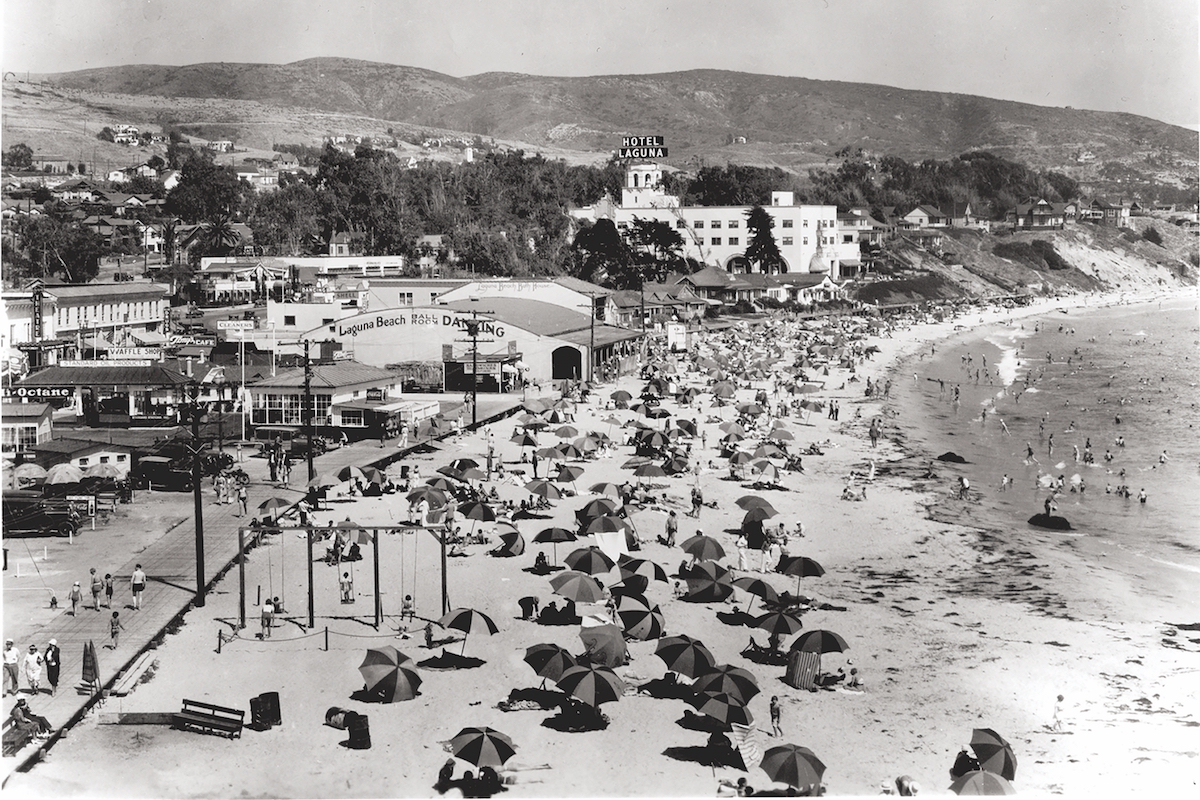

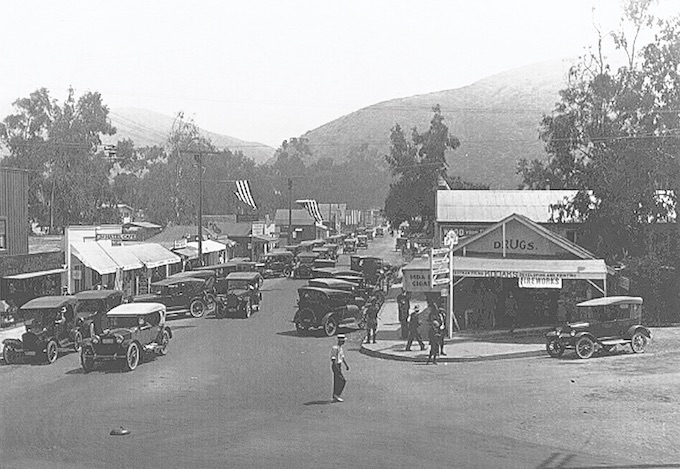

Back in the early days, Laguna Beach didn’t have a single traffic light or even a stop sign—except for one that was rolled onto Coast Highway on weekends so that people could cross the road at Ocean Avenue. Main Beach was lined with buildings, from restaurants to a dance hall and even private homes, so those driving by didn’t have the stunning Window to the Sea that exists now. And the unpaved highway didn’t even connect to Newport Beach.

On the homefront, ice was delivered each morning to keep your food cold in an “ice box” since electric refrigerators were not readily available or affordable. And water was trucked up to the few people who lived on Top of the World. Yet, some things were more formal: The local lumber delivery driver wore a coat and tie. And, with fewer residents, it seemed like everybody knew everybody else in town.

“See, in those days, it was just different. … The culture was different. It wasn’t like it is today,” says Dick Metz, 93, who was born in 1929—just two years after the city was incorporated and on the brink of the Great Depression. “… You can show pictures, but there’s a story behind it. I think it’s important to keep the history [alive].

“… I guess the reason I’m so interested is I could be gone tomorrow and my mind remembers all this. And I don’t think there’s anybody that I know of [who was in Laguna during that time]. … I’m the only one left in my high school class and the classes below me.”

The lifelong Laguna resident—a surfer whose world travels would later help inspire “The Endless Summer” film and who went on to establish the Surfing Heritage and Culture Center in San Clemente—had a front-row seat to much of the town’s goings-on back then. His dad, Carl Metz, owned the Laguna Diner in an old railroad car and then The Broiler, both situated at Main Beach. There were plenty of shenanigans by local characters. And famous actors from Bing Crosby to Bob Hope, Victor Mature and Bette Davis would stop to eat there on the way to the Del Mar racetrack on weekends.

“The movie stars weren’t like they are now. They weren’t so aloof,” Metz recalls. “You know, they were regular people that had a little bit better jobs than everybody else. They’d come in and just kind of join in the camaraderie of the local people.”

Metz specifically recalls one pint-sized actress, curly-haired Shirley Temple, who was about the same age as him and often visited with her parents in the summer. “This is when I was 5 or 6. Shirley’s mom and dad would bring her down and they would always eat at The Broiler. And they got to know my mom and dad, so they would sit in the booth and socialize. … They’d say, ‘You and Shirley, go out on the beach and play.’ ”

Metz also got to be a child star of sorts and helped usher in a beloved local tradition. “I was in the first living pictures [now called Pageant of the Masters]. … It was only a week long and it was all done with Laguna volunteers,” says Metz, who portrayed a kid in a Norman Rockwell painting back when the show took place in a vacant lot where Las Brisas restaurant is now.

Depression-Era Days

Metz’s parents, Carl and Edna May, were from Pomona and then lived in Big Bear before moving to Laguna where Carl had the opportunity to buy the diner in town. Edna May worked as a grammar school teacher when the lower grades were taught in the same building as the high school on Park Avenue. Then she helped as a cashier at the restaurant after classes let out in the afternoon. “See, in those days, you worked all the time,” Metz says, noting that Sunday was the only day off for attending church and spending time with family.

Even though Metz was a kid, he worked, too. “This was all during the Depression, so nobody had any money and I sold newspapers,” he says of hawking the Los Angeles Times on the corner by his dad’s restaurant. “… In those days, the attitude, the culture, the mentality was you gotta learn to work and be a worker.” He recalls the truck rolling by—without stopping—and tossing out a wire-wrapped bale of papers onto the sidewalk. “They were 10 cents and I got a penny for selling one,” Metz says. “… I had to earn $2.50 for the whole summer—that’s how much a pair of Levi’s cost—and my mom would drive me to Santa Ana, because you couldn’t get them in Laguna. … Every September I would buy a brand-new pair of Levi’s for $2.50 that I had earned selling newspapers.”

Another job (although he didn’t get paid for it): Around age 12, he would watch the bar at the restaurant for a few minutes here and there, getting customers a beer if they came in when his dad had to run an errand. Later, as a teenager, he’d start learning to bartend; the rules weren’t as strict back then. Since he spent so much time in the restaurant and bar, eating all his meals there and helping out, Metz was witness to a lot of local happenings.

Colorful Characters

In addition to Hollywood actors, some of the artists who worked on the movie sets would come to Laguna. “One of the artsy guys, … he had a bulldog named Jigs and he would come down every weekend and come to the bar … and he would bring Jigs along,” Metz says. “And he’d come and say, ‘Hey, Dick, I want a case of Acme [beer]. … He’d always bring a pie pan and he’d have one bottle of beer and he’d give Jigs another bottle. And the two of them would drink the entire case of that beer. … He’d have to carry Jigs [home]—he couldn’t walk, he was so drunk.”

Metz recalls another guy, a lightweight boxing champion named Charlie Furlong, who worked as an engineer building highways and bridges in Brazil before returning to Laguna where he lived at Top of the World. “Every time he would come back from Brazil, he’d bring an animal,” Metz says. “And he brought a parrot one time, and he’d come into the bar with a parrot on his shoulder and the next time it would be a monkey. And I remember so well, he brought in a black panther on a leash. A black panther! … He tied up the panther in a booth … [to the] round pillar holding up the table. … And the panther would just get up on the Naugahyde booth and, unbeknownst to me or Charlie Furlong, … he started clawing and eating the Naugahyde.”

Metz also remembers when Dick Smith, the son of Pappy Smith (who owned the Coast Inn), became the city’s first motorcycle cop. He rode a Harley-Davidson and would often park it near The Broiler, sitting inside the door and drinking coffee—since the stop sign would get rolled out right in front of the restaurant—and watch for people to speed past the sign. Then he’d hop on the bike and pull them over down the street. One day, Metz says, his dad, Furlong and a local painter in town were at the bar and asked Dick Smith if they could ride his motorcycle around the block. He agreed and comedy ensued. “They said, ‘Let’s see who can drive the motorcycle … with your cocktail resting on the gas tank.’ ”

But those friendly bets weren’t the only gambling in town. Metz’s uncle came to work at the dining car (before The Broiler took its place), washing dishes during the Depression. To make extra money, he asked if he could set up a punchboard at the counter. A punchboard was about a foot square and was covered with little holes. It cost a nickel for the opportunity to punch out one of the holes with a small metal stick, revealing a piece of paper that said if you won any money. Punchboards evolved to machines featuring card games and then, finally, slot machines came out. Metz’s uncle introduced the first slot machines in Orange County, putting them in the Laguna Diner and a downtown drug store. But the line of people waiting to play spilled out onto the sidewalks and across the street, leading the City Council to ban slot machines. “It was so crowded that they had to outlaw it because it was stopping traffic,” Metz says.

A Popular Place

For spring break, Metz recalls crowds would flock to town, renting little tents that filled campgrounds on Broadway where Coast Hardware is now and where the Glenneyre Street parking structure is behind Peppertree Lane. “They were just side by side and they had a wooden floor. … I don’t know how much they were, but there were rows of them,” Metz says, adding that the young college-aged partiers would drink and make a ruckus. “… It was just a wild kind of time.”

In the 1920s and 1930s, Laguna was getting busier and busier as improvements made it easier for people to come to town. “I watched them pave the Coast Highway and it took them a week to pave a block,” Metz says. “Every block, I put my initials in for a mile down the Coast Highway. It used to be a two lane, just had tar on it and it was terrible, but then they paved it and made it four lanes. And that was about, I’m going to say, 1936 or ’37—I don’t know exactly.”

Once the highway to Newport was paved, visitors could take the Pacific Electric Railway’s Red Cars on a track from LA to Newport, then drive to Laguna. “That’s when the movie stars started coming down and the Del Mar racetrack started,” Metz says. “And the Festival of Arts [was going on], … so Laguna was booming in those days. And then the war started and that changed everything.”

During World War II, they had barbed wire on the Main Beach, Metz recalls. “You couldn’t even go to the beach,” he says. “And they had Coast Guard guys with bayonets patrolling it. But that was only at first. That wasn’t during the whole war. But they were afraid the … [Japanese] were going to invade.”

And, of course, there was rationing like everywhere else in the country. But, since Laguna was a coastal city, extra precautions were taken for security. Right after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii on Dec. 7, 1941, cannons and other artillery were set up at Top of the World in Laguna, with a communications center located downtown where the police station is now. “I was a messenger for the Army. They took the high school track guys and they didn’t have any radios or telephones … [so] we had the best relay team in Laguna’s history. They gave us white Army helmets, which I still have with a lightning bolt on it and we would run from the Top of the World in relays down to the police station sending messages.”

Once WWII was over, people started to have more free time and surfing took off with the war-time invention of materials that made for better boards. Metz has plenty of stories about surfing’s heyday, too, but that’s a tale for another time.